ART REVIEW James Turrell: A Retrospective @ LACMA

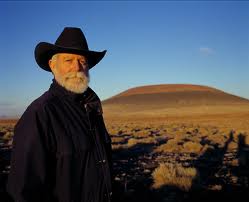

Promises of ethereal delights are incredibly seductive to us mere mortals. For artist James Turrell they have yielded earthy rewards, as three major US museums mount tributes to his work this year. The white-bearded artist intones that in his work light “is not the bearer of revelation — it is the revelation,” causing seekers to flock to NYC, Houston and Los Angeles.

James Turrell: A Retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is the most comprehensive survey of the artist’s work to date. Including early prints, photographs, and eleven “sensory environments” or installations. The museum dedicates two rooms to what it considers Turrell’s masterpiece, Roden Crater, a land art project on the site of an extinct volcano in Arizona. The documentation of Turrell’s 30-year effort to transform the crater’s cone into a naked-eye observatory offers the general public a peek into the invitation-only site.

Born in 1943 in Los Angeles, Turrell was a key member of the Southern California Light and Space movement of the 1960s and ’70s inspired by the region’s luminosity. Turrell’s love affair with light was sparked by a college lecture so boring he fixated on the glow emanating from the professor’s slide projector. Influenced by perceptual psychology, astronomy, mathematics and aviation - science is Turrell’s muse.

From first sight, Turrell’s affinity for mathematics is irrefutable. Curves are hard to find in his work. Turrell embarked on his pioneering light experiments in 1966 in his famed Santa Monica studio. By blacking out all natural light, Turrell was able to manipulate light sources with varying degrees of intensity. These early experiments are brought to life through the linear photo series Music for Mendota and aquatint prints First Light and Still Light.

Atrium (White), a projection of pure white light into the corner of a darken room creates the illusion of a floating cube. It is the simplest, yet most compelling work in the exhibition. Despite being one of Turrell’s earliest installations, Atrium remains fresh because it contains a balance of light and dark, yin and yang. Color selection plays a starring role in Turrell’s light abstractions. Raemar Pink White feels like stepping onto a ballet-slipper-pink cloud. Emanating from behind a rectangular plane, the soft pink light feels sugary. Yet, just like chewing a piece of bubble gum, the taste flattens the longer you chew. Recommended times for experiencing the installations are 8 to10 minutes, but I found the longer I stayed, the duller my experience became.

The immersive room installations, Key Lime and St. Elmo’s Breath, feature pitch-black rooms, velvet drapes and black carpets. They also introduce eye-catching color palettes and visual tricks, which did slightly shift my visual orientation. However, sitting in the dark, admiring the pretty colors, the experience felt familiar even without a cocktail in hand.

Throughout human history capturing the aesthetics of light has served as a metaphor for communion with the divine. Turrell’s goal “to bring the cosmos close” continues in that tradition. His Skyscapes, site-specific buildings, are designed with open ceilings to present the sky as a flat plane of color or a moving painting. A slide projection of Turrell’s 75 Skyscapes, scattered across the globe, suggest the artist works best when complimenting the atmospherics provided by Mother Nature.

Turrell claims that he creates experiences that allow viewers to “see themselves see.” This grandiose statement may set visitors up for disappointment. If Turrell’s elaborate installations are meant to create doorways to the spiritual, they are cramped by the curious absence of soul. While Turrell’s works contain the elegance of a mathematical equation, they lack joy. The highly choreographed museum experience also doesn’t help lighten the mood.

The most extreme examples of Turrell’s left-brain approach to art-making are his recent works, which rely on “sensory deprivation” to disorient the viewer’s optical perception. Both Dark Matters and Light Reignfall (of the Perpetual Cell series) require visitors to sign liability waivers in the event they are emotionally or physically harmed. Turrell himself describes these works as “invasive” and “oppressive,” which hasn’t stopped plenty from signing up for them.

It seems Turrell’s single-minded focus has landed him in a bubble. Once pioneering, his light installations now feel ubiquitous. While good art requires skill, great art goes deeper and lasts longer.

Maryna